Women Inventors

"Lest We Forget"

by Dr. Lenwood Davis

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2006. Revised by SLNC Government and Heritage Library, June 2023

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

North Carolina has been home to women inventors throughout history. Even before the Civil War (1861–1865), one woman from the Tar Heel State received a United States patent. In 1834 Ethel H. Porter, of Lincolnton, patented her invention related to cutting feed for horses and cattle. This was the first known patent issued to a North Carolina woman. In 1859 Abigail Carter, of Clinton, invented a pair of overalls designed for her husband, who was a railroad engineer. These sturdy overalls wore so well that other railroad men began asking for them. Carter opened a business and became the first manufacturer of overalls in the United States. During the Civil War, Anna Lewis, of Greensboro, wanted to contribute to the Confederate cause, so she invented a machine for ginning, carding, and spinning cotton. The Confederate Patent Office issued Lewis a patent for her invention in 1864.

North Carolina has been home to women inventors throughout history. Even before the Civil War (1861–1865), one woman from the Tar Heel State received a United States patent. In 1834 Ethel H. Porter, of Lincolnton, patented her invention related to cutting feed for horses and cattle. This was the first known patent issued to a North Carolina woman. In 1859 Abigail Carter, of Clinton, invented a pair of overalls designed for her husband, who was a railroad engineer. These sturdy overalls wore so well that other railroad men began asking for them. Carter opened a business and became the first manufacturer of overalls in the United States. During the Civil War, Anna Lewis, of Greensboro, wanted to contribute to the Confederate cause, so she invented a machine for ginning, carding, and spinning cotton. The Confederate Patent Office issued Lewis a patent for her invention in 1864.

During the 1860s, several other women in the state received patents for their inventions. One such woman was Nannie W. Hunter, of Elizabeth City. She was not satisfied with the smell of soap and therefore went about improving it. In 1867 Hunter received a patent for her improvement in the manufacture of soap. Another inventor of this period was Harriet Morrison Irwin, of Charlotte, who designed a hexagonal house and in 1869 became the first woman in the United States to patent an architectural innovation.

In the 1800s North Carolina women received patents for new ideas and improvements in household items such as table easels (1877), a corset (1884), grate and fireplace cornices and a mantel protector (1889), and a cushion holder (1895). They also patented items ranging from a market truck (1883) to a clamp (1894).

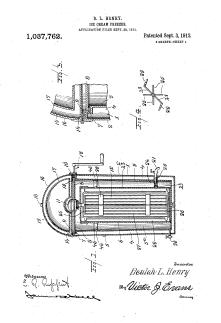

Of all the women inventors in the United States, the one who invented more items than any other probably was Beulah Louise Henry. A granddaughter of North Carolina governor W. W. Holden, Henry was born in Raleigh in 1887, attended Presbyterian and Elizabeth colleges in Charlotte, and lived most of her adult life in New York City. Even as a child, Henry often sketched out her ideas for inventions. Later she reportedly made models of her ideas from bits of soap, tape, hairpins, buttons, rocks, and other items at hand. At age twenty-five, in 1912, she received her first patent, for a vacuum-sealed ice cream freezer. A year later, she invented a new kind of handbag. One of her most well-known inventions was a parasol, or umbrella, that came with various snap-on covers. (Users could change covers to match their outfits.) One manufacturer told Henry that such an umbrella could not be made. She did not believe him and went on to prove him wrong, inventing a process that earned her about $50,000 from the manufacturer. She spent most of her life proving men wrong about her ideas. Once asked why she was an inventor, Henry replied that she simply could not help it. Invention came naturally to her.

Henry blazed trails for other women. During her lifetime, her inventions were available in several foreign countries, she was president of at least two corporations, and several major publications featured stories on her. She had more than one hundred inventions— including a hair curler, dolls with moving eyes, soap-filled sponges for children, and items related to sewing machines and typewriters—to her credit, with about forty-nine patented, the last in 1970. Some people called Henry, who died in 1973, the “Lady Edison.”

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner—born in Monroe, near Charlotte, in 1912—likely was the second most productive woman inventor from North Carolina. Between 1956 and 1987, Kenner received five patents for household and personal items, including a carrier attachment for a walker (1959), a bathroom tissue holder (1982), and a back washer mounted on a shower wall and bathtub (1987). She did not make much money from her efforts, but she said that she was more concerned with making life easier for people than with getting rich.

At one time, many people believed that the role of a woman was mainly that of wife and mother. Society did not give women the same chances to become educated or to express themselves as it gave men. Women were expected to channel their creativity into quilting, sewing, cooking, and other ways considered within the bounds of their gender. They could not own property in their own names and rarely had the money or time to pursue something like a patent. Therefore, women were limited in what they could do. Since laws and times have changed, giving women more rights and opportunities, their growing contributions to the science and invention have made people’s lives easier and better.

At the time of this article’s publication, Dr. Lenwood Davis was an adjunct professor in the Department of English and Foreign Languages at Winston-Salem State University and the author of an upcoming book on North Carolina inventors.

Additional resources:

Blashfield, Jean F. 1996. Women inventors 4: Sybilla Masters, Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner and Mildred Davidson Austin Smith, Stephanie Kwolek, Frances Gabe. Capstone short biographies. Minneapolis, MN: Capstone Press.

Camp, Carole Ann. 2004. American women inventors. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers.

Sullivan, Otha Richard, and James Haskins. 2002. African American women scientists and inventors. New York: Wiley.

1 January 2006 | Davis, Lenwood