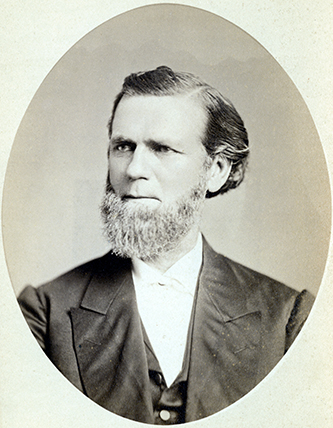

Craven, Braxton

26 Aug. 1822–7 Nov. 1882

Braxton Craven, educator, Methodist minister, and Mason, was a native of Randolph County. His mother was Ann Craven and his father, according to the Reverend D. V. York, was Braxton York, a cousin of Brantley York, the founder of Union Institute and father of D. V. York. At the age of seven Craven was taken into the home of a Quaker neighbor, Nathan Cox, an enterprising man who combined several other occupations with farming. Craven lived with Cox for nine years, indicating later that he was "sorely oppressed" in his youth, but that he learned industry, thrift, and self-reliance and developed a spirit of faith, optimism, and cheerfulness.

Braxton Craven, educator, Methodist minister, and Mason, was a native of Randolph County. His mother was Ann Craven and his father, according to the Reverend D. V. York, was Braxton York, a cousin of Brantley York, the founder of Union Institute and father of D. V. York. At the age of seven Craven was taken into the home of a Quaker neighbor, Nathan Cox, an enterprising man who combined several other occupations with farming. Craven lived with Cox for nine years, indicating later that he was "sorely oppressed" in his youth, but that he learned industry, thrift, and self-reliance and developed a spirit of faith, optimism, and cheerfulness.

At the age of sixteen, Craven struck out on his own. Although he had had little formal schooling, he chose to be a teacher and the following year started a subscription school. After two years of teaching and working during vacation, he was able to attend New Garden School (now Guilford College) for two academic years. Then he became assistant teacher at Union Institute, a school organized in his home county in 1838 by a group of Quakers and Methodists. Upon Brantley York's resignation in 1842 as the first principal of the school, Craven succeeded him. Wishing to upgrade the institute from an academy and recognizing that the first requirement for improved common schools in North Carolina was better-educated teachers, he started a program of teacher training.

In 1849, Craven improved his own academic standing by passing the examination on the entire course of study at Randolph-Macon College; he was awarded an honorary A.B. degree. Two years later both Randolph-Macon and The University of North Carolina conferred upon him an honorary A.M. degree, and later he received the D.D. degree from Andrew College in Tennessee and the LL.D. degree from the University of Missouri.

In 1850, Craven and Reuben H. Brown launched the Southern Index in Asheboro. This was an educational journal in which Craven set forth his ideas about the training of teachers and the common schools. After several months it became a literary magazine, with the title Evergreen. It ran for twelve issues and carried two novels by Craven that later appeared in book form as Mary Barker and Naomi Wise, under the pseunonym Charlie Vernon.

Having become acquainted with the normal school movement in the country, Craven decided that a normal college should be started in North Carolina. He succeeded in getting a bill passed in the General Assembly in 1851, incorporating Union Institute as Normal College. The bill provided for state support, but the legislature refused to vote the funds, although it did grant Normal College graduates the privilege of teacher certification without examintion. In another vain attempt to secure state support for Normal, Craven joined with Wake Forest and Davidson in asking the legislature to establish scholarships for training teachers at all three colleges. He succeeded in getting Normal's charter amended in 1853 to make it a state school, but the only financial support he received from the state was a loan of ten thousand dollars from the Literary Fund at 6 percent interest. This loan he ultimately paid back himself.

Little actually came of Craven's experiment in teacher training. Under the amended charter, Normal College could grant academic degrees, but after a few years of turning out poorly educated teachers and receiving widespread criticism for doing so, Craven decided to deemphasize the teacher-training program and concentrate on developing a regular collegiate curriculum. He never ceased, however, to lend assistance to the cause of public education.

Discouraged by the lack of tax support for Normal College and by the opposition of educational leaders of the state, Craven turned elsewhere for help. He persuaded the North Carolina Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, to adopt Normal in 1856 as its college. Three years later the name of the college was changed to Trinity, and, except for two years in the mid-1860s, Craven continued as its president until his death.

Craven was initially a Unionist that opposed secession, but his support for the South and slavery remained strong. He supported the Confederate government when it finally seceded. When the Civil War began, Craven organized a company of young men he called the Trinity Guard to prevent the total disruption of the college. He also instituted a course in military training for the summer of 1861. Later that year he and the guard were assigned to the Confederate prison at Salisbury. He retained the presidency of Trinity and returned there after about a month as commander of the prison.

Trinity College was financially insecure during Craven's presidency, in part because of a schism in the North Carolina Conference that began in the late 1850s over support of the college and its administration. Criticism of Craven finally led to his resignation on 1 Jan. 1864. After the war, however, he was persuaded by the conference to return and reopen the college, which had closed in April 1865, in January 1866.

Although he became a college administrator and preacher, Craven never gave up teaching. As a public speaker, preacher, and leader of Methodism in North Carolina, he became widely known. He was licensed to preach in 1840 and nineteen years later was admitted to full connection in the North Carolina Conference. He served the conference as secretary and in other ways, but he held only one pastorate, the Edenton Street Methodist Church in Raleigh in 1864 and 1865. Craven was known to negotiate with enemies in the North Carolina Conference. After the Civil War, he also urged for the reunification of the Methodist church.

On 26 Sept. 1844, Craven married Irene Leach, the first female graduate of Union Institute and a teacher in the school. He operated a farm on the side to support his growing family, which came to include two daughters and two sons, Emma Lenora, James Lucius Melville, Willie Oscar, and Sallie Kate. Additionally, Craven was an enumerated enslaver prior to the Civil War. Two notable children Craven enslaved were named Isam (noted as part of the Craven household in 1854) and Malinda (1857). Craven intended to purchase and enslave more children, but was disincentivized by the "high prices" of Isam and Malinda.

Craven was buried in the village that grew up around Trinity College, which also took the name of Trinity.

References:

Nora C. Chaffin, Trinity College, 1839–1892 (1950).

John F. Crowell, Personal Recollections of Trinity College (1939).

Jerome Dowd, The Life of Braxton Craven (1939).

Duke University Archives (Durham), for Braxton Craven Papers and various publications.

Manuscript Department, Library, Duke University (Durham), for Craven-Pegram Family Papers and Charles Alexander Long Papers.

Additional Resources:

Activating History for Justice at Duke: A Report by Constructing Memory at Duke. Duke Human Rights Center: Durham, NC. 2015. https://www.activatinghistoryatduke.com/uploads/8/9/2/3/89234082/print_a...

"Duke University: A Brief Narrative History." Duke University Libraries. September 21, 2020. https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/uarchives/history/articles/narrative...

"Duke's Presidents." University Archives in the Daniel B. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University. http://library.duke.edu/uarchives/history/presidents.html#Craven (accessed May 13, 2013).

King, William E. "Braxton Craven, 1822-1882." If Gargoyles Could Talk: Sketches of Duke University. Carolina Academic Press. 1997. http://library.duke.edu/uarchives/history/histnotes/b_craven.html (accessed May 13, 2013).

Gillispie, Valerie. "President, Astronomer: How a solar eclipse confirmed Braxton Craven’s perfect timing." Duke Magazine. August 8, 2012. http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/president-astronomer (accessed May 13, 2013).

Ivey, Thomas N. "Braxton Craven." Biographical history of North Carolina from colonial times to the present volume 4. Greensboro, N.C.: C. L. Van Noppen. 1906. 102-111. https://archive.org/stream/cu31924092215460#page/n165/mode/2up (accessed May 13, 2013).

Chaffin, Nora C. "A Southern Advocate Of Methodist Unification In 1865." North Carolina Historical Review 18, no. 1 (January 1941). 38-47. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/north-carolina-historical-review-1941-january/3705564 (accessed May 13, 2013).

Image Credits

"Braxton Craven, undated." Photograph. Flickr. Duke Yearlook / Duke University Archives. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dukeyearlook/3330451641/ (accessed May 13, 2013).

1 January 1979 | Russell, Mattie U.