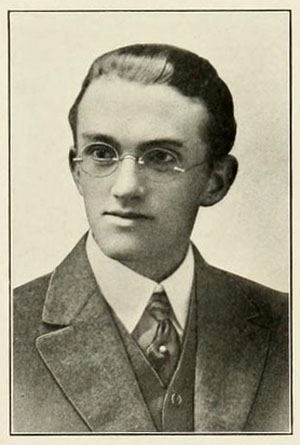

McCall, Frederick Bays

7 Oct. 1893–8 Apr. 1973

Frederick Bays McCall, professor of law, was born in Charlotte, the son of Johnston Davis and Sallie Lee Nooe McCall. His father was a leading member of the Mecklenburg County bar for a half century and at one time served as mayor of Charlotte. Young McCall entered The University of North Carolina in 1911 and received an A.B. degree in the classics in 1915. Following graduation he taught Latin and mathematics in the Charlotte High School. In 1918 he resigned his teaching position to become assistant secretary of the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce. Some months later, he was elected principal of the Charlotte High School; he served in that post for two years before returning to Chapel Hill to study law.

Frederick Bays McCall, professor of law, was born in Charlotte, the son of Johnston Davis and Sallie Lee Nooe McCall. His father was a leading member of the Mecklenburg County bar for a half century and at one time served as mayor of Charlotte. Young McCall entered The University of North Carolina in 1911 and received an A.B. degree in the classics in 1915. Following graduation he taught Latin and mathematics in the Charlotte High School. In 1918 he resigned his teaching position to become assistant secretary of the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce. Some months later, he was elected principal of the Charlotte High School; he served in that post for two years before returning to Chapel Hill to study law.

After one year of formal study, McCall passed the bar examination and began to practice law with his father in Charlotte. In a few months, he accepted a position at the university teaching Latin. While on campus, he also attended classes in the law school. At the end of the year, he returned to Charlotte to resume the practice of law with his father. In 1926, when the dean of the law school became ill, The University of North Carolina asked McCall to pinch-hit for him. Dean Lucius McGehee died shortly thereafter and McCall was chosen to replace him on the faculty.

In 1927–28 he took a leave of absence to attend Yale Law School, where he completed his work for the J.D. degree in 1928. This was a vintage year in the life of Fred McCall. Returning to Chapel Hill, he married Adeline Denham, the niece of Professor Frederick H. Koch, who founded the Carolina Playmakers. Thus he began his thirty-eight-year career as a permanent member of the law school faculty and his forty-five-year marriage to a talented teacher of music.

At the law school, McCall first taught courses in common-law pleading, torts, damages, sales, domestic relations, equity, corporations, and civil procedure. Later he specialized in the field of property, including real property, personal property, titles, wills and administration, and future interests.

A crowning achievement in his career was the enactment of a new Intestate Succession Act in 1959 by the North Carolina General Assembly. The impetus for this legislation began in 1933 when changes were recommended by McCall and Allen Langston, a former student, in an article published in the North Carolina Law Review. This led to the authorization of a study commission by the General Assembly in 1935 on which McCall served at the appointment of Governor J. C. B. Ehringhaus. The commission, which was chaired by Senator Carl L. Bailey, produced far-ranging proposals to reform the law of intestate succession, administration of estates, wills, and guardianships. A 195-page bill passed the senate but failed enactment by a single vote in the house of representatives. Rather than returning to the drafting board, McCall went back to the classroom to teach more students about the need for law reform. In 1957 the General Assembly appropriated funds to enable the General Statutes Commission to recommend changes in the laws relating to intestate succession. The commission appointed McCall, Professor Norman A. Wiggins of the Wake Forest Law School, and Professor W. Bryan Bolich of the Duke University Law School as a special committee to prepare new legislation. The work of the committee was approved by the General Statutes Commission and submitted to the General Assembly. This time the legislature was prepared to adopt a modern law of intestate succession, which included equal inheritance rights for women among its many salient features, and the bill passed without difficulty.

In 1961 the General Statutes Commission again called upon McCall, Wiggins, and Bolich to produce proposals for a new law on the estates of missing persons. Based on the recommendations of the special committee and the General Statutes Commission, a new law was enacted in 1965. In the latter year, the special committee turned its attention to the complex task of revising the law on the administration of estates. McCall was the only member of the original committee to serve until this work was completed. In 1974 the General Assembly, with minor exceptions, approved the proposed legislation of more than one hundred pages.

McCall was a careful thinker and wrote with clarity, precision, and accuracy. His articles for the North Carolina Law Review, beginning with volume 1 in 1922 and concluding with volume 44 in 1966, were solid and substantial contributions to legal scholarship. These included "Appellate Practice and Procedure in North Carolina" (vol. 7, 1928), "The Family Automobile" (vol. 8, 1930), "The Torrens System—After Thirty-five Years" (vol. 10, 1932), "A New Intestate Succession Statute for North Carolina (with Allen Langston; vol. 11, 1933), "The Destructibility of Contingent Remainders in North Carolina" (vol. 16, 1937), "Estates on Condition and on Special Limitation in North Carolina" (vol. 19, 1941), "Some Problems in Administration of Estates" (vol. 35, 1957), "North Carolina's New Intestate Succession Act" (vol. 39, 1960), and "Estates of Missing Persons in North Carolina" (vol. 44, 1966).

Through unwavering interest and devotion, and a sustained and painstaking approach, McCall was for many years the premier authority on North Carolina law in the fields of real property, wills, and decedents' estates. He was a member of the Order of the Coif, Phi Delta Phi, Sigma Chi, and Phi Mu Alpha. In 1971 four hundred attorneys in the state awarded him the Silver Urn in recognition of his achievements in teaching, research, and public service relating to the law of real property.

Fred McCall had a great capacity for loyal friendships. A gentle man, he could be firm in expressing his thoughts on controversial matters but always sought ways to avoid giving personal offense. He was a talented musician, and his performance as a timpanist graced many a symphonic concert. Love of music was a bond he shared with his wife, Adeline. He was buried in Chapel Hill where he worked and lived for fifty-two of his seventy-nine years.

References:

Jacques Cattell, ed., Directory of American Scholars, vol. 4 (1963).

Records, Alumni Office and Office of the Secretary of the Faculty (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

Additional Resources:

North Carolina General Assembly. Resolution 1973-99 (House Joint Resolution 1240). 1973. Session. http://www.ncga.state.nc.us/EnactedLegislation/Resolutions/PDF/1973-1974/Res1973-99.pdf (accessed October 2, 2014). [Resolution regarding the death of Frederick Bays McCall.]

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina. https://archive.org/details/universityofnort321univ (accessed October 2, 2014).

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "The One Hundred and Twentieth Annual Commencement : Memorial Hall : Wednesday June 2, 1915." Chapel Hill, N.C. 1915. https://archive.org/details/commencement19151915univ (accessed October 2, 2014).

Image Credits:

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Dialectic and Philanthropic Literary Societies and the Fraternities. The Yackety Yack, Volume 15. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 1915. 67. http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/ref/collection/yearbooks/id/874 (accessed October 2, 2014).

1 January 1991 | Aycock, William B.