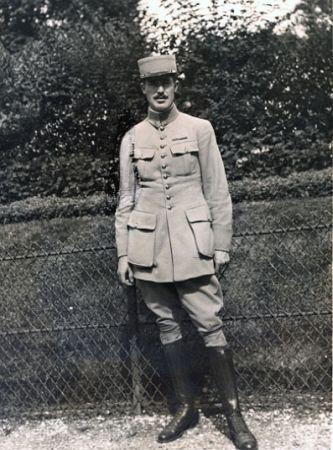

Kiffin Rockwell: “Aristocrat of the Air”

Kiffin Yates Rockwell was born in Newport, Tennessee, on September 20, 1892. He was the son of James Chester Rockwell, a Baptist minister, and Loula Ayers Rockwell. His name reflected his father’s knowledge of religious history. “Kiffin” came from William Kiffin, an English missionary in the 1400s. “Yates” honored Matthew Yates, a missionary from North Carolina in the 1800s. The family name was traced to a French nobleman, Ralph de Rocheville. This connection to France later played a very important part in Rockwell’s life.

Kiffin Yates Rockwell was born in Newport, Tennessee, on September 20, 1892. He was the son of James Chester Rockwell, a Baptist minister, and Loula Ayers Rockwell. His name reflected his father’s knowledge of religious history. “Kiffin” came from William Kiffin, an English missionary in the 1400s. “Yates” honored Matthew Yates, a missionary from North Carolina in the 1800s. The family name was traced to a French nobleman, Ralph de Rocheville. This connection to France later played a very important part in Rockwell’s life.

While Rockwell was still in elementary school, his mother moved the family to Asheville. His father had died earlier at the age of twenty-six. Rockwell grew up hearing old-timers spin tales of daring and adventure. He was born with a restless spirit, and something inside of him badly wanted to share the excitement of those pioneer days.

His wishes came true as war clouds gathered over Europe in the summer of 1914. Rockwell believed, perhaps even hoped, that fighting was about to begin. He already admired the French because of his family heritage, and the possibility of combat offered the adventure he craved. On August 3, 1914, Rockwell became the first North Carolinian, and some say the first American, to volunteer for French service. Despite his personal desire for excitement, he viewed the war as more than a great adventure and more than just an effort to save France. There was a higher goal at stake—the cause of humanity itself. He believed the Germans posed an evil threat to the ideals of mankind, and he felt obligated to help stop them. He explained his belief in a letter to his mother: “If I die, you will know that I die as every man should—in fighting for the right.”

While serving with the First Regiment of French Legionnaires, he was wounded and spent six weeks in a hospital at Rennes. There he heard vivid descriptions of air combat, and they appealed to his daring personality. Rockwell requested a transfer to the Caulder Squadron where he received brief training as a pilot. The French government kept Rockwell and other American pilots grounded for nearly six months. Then, on April 20, 1916, they were allowed to form the American Escadrille (squadron). Four weeks later, Kiffin Rockwell became the first member of his unit, and the first American pilot, to shoot down an enemy plane.

Six days after his first “kill,” Rockwell was in action over the battlefield at Verdun. Though his unit was outnumbered, Rockwell refused to run for safety. Bullets riddled his plane, and one exploded after piercing his wind visor. Bits of glass and steel tore into his face. With blood-spattered goggles and in intense pain, Rockwell continued the fight until he could return to his home base.

Rockwell spent more than his share of time in the air. In July and August of 1916, he flew seventy-four missions. Overall, he took part in 141 battles and earned the unofficial title “Aristocrat of the Air.” Along the way he was awarded the Médaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre, the highest honors an American in French service could receive. Jim McConnell of Carthage, a fellow Tar Heel in the escadrille, said of young Rockwell, “When Kiffin was over the lines, the Germans did not pass—and he was over them most of the time.” But war has a quickly changing face, turning today’s victory into tomorrow’s defeat.

On September 23, 1916, Rockwell was returning from a mission when he spotted an unescorted German Aviatik bomber behind French lines. He dived at the rear of the plane, either forgetting or neglecting the fact that Aviatiks carried tail gunners. An exploding bullet ripped into Rockwell’s chest at the base of his throat, and he died instantly. Rockwell’s plane spiraled two miles to the ground, crashing near the spot where his first victim had come to rest. His commanding officer, Captain Thénault, tearfully reported to Rockwell’s fellow pilots, “The best and bravest of us all is no more.” He was three days past his twenty-fourth birthday.

Widespread publicity of his adventures made Rockwell a national hero. The image of a courageous young man fighting and dying for an ideal inspired thousands of followers who volunteered for the war against Germany. Rockwell captured the imagination of the American people, produced a frenzy of volunteers, and helped to shake the United States out of its position of neutrality in the European conflict.

At the time of this article’s publication, Jerry L. Cross served as a research historian in the Research Branch of the Division of Archives and History.

Additional resources:

"Kiffin Y. Rockwell, World War I Aviator." Virginia Military Institute Archives. http://www.vmi.edu/archives.aspx?id=12371

"Kiffin Rockwell: The Carolinas' First Lost Hero in WWI." Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/rockwell.html

"Kiffin Rockwell." North Carolina Centennial of Flight. State Archives of North Carolina. 2003. http://exhibits.archives.ncdcr.gov/ffc/Flight/Aviation/Kiffin_Rockwell.html (accessed November 1, 2013).

"Kiffin Y. Rockwell." North Carolina Highway Historical Markers. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?ct=ddl&sp=search&k=Markers&sv=P-44%20-%20KIFFIN%20Y.%20ROCKWELL

Sistrom, Mike. "North Carolina's World War I Aviators." Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/mcconnell/support1.html

Image credit:

"Rockwell in Paris." 1916. Virginia Military Institute Archives. Online at http://www.vmi.edu/archives.aspx?id=12371. Accessed 8/31/2012.

1 May 1993 | Cross, Jerry L.