Clapper Rail

Rallus longirostris

by Joe Fuller

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Classification

Class: Aves

Order: Gruiformes

Average Length

13 in.–16 in.

Food

Crayfish, small crabs, small fish, frogs, slugs, snails, aquatic insects, grasshoppers and seeds of weeds and woody plants. At least 79% of the year-round diet is animal-based.

Breeding

Monogamous: Pairs are established or reestablished each year. Nesting season runs from April to June. Incubation period is 20 days with a possibility of 2 clutches in a nesting season.

Young

From 6–14 young, usually 9–12. Chicks are precocial; fed regurgitated pellets shortly after hatching, later collecting own food. Adult plumage acquired in October of first year.

Life Expectancy

Not well documented.

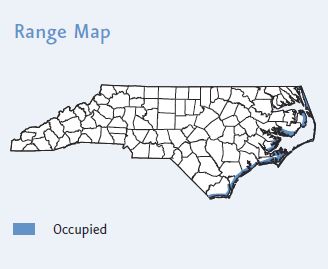

Range and Distribution

The range of the clapper rail includes the Atlantic, Gulf and California coasts, Central America, the Caribbean, and coastal South America. In North Carolina, clapper rails are found exclusively in coastal salt marshes. In winter, North Carolina has both a year-round resident population and a migrant population made up of birds from northern locations. Rails usually migrate at night, flying south along the coast. Recent analysis of observations indicate that highest densities occur from Florida to southern North Carolina.

General Information

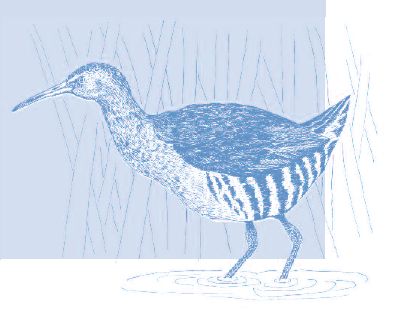

A raucous chock-chock-chock… or a fleeting glimpse of a gray and brown bird slinking through marsh grass is sometimes all you will experience of the secretive clapper rail. This bird is normally found in the coastal salt marshes of North Carolina’s easternmost counties. Hen-like in appearance, the clapper rail is locally known as the marsh hen. The saying “thin as a rail” comes from the bird’s lean body, a characteristic that enables it to slip easily through marsh grass when walking or trying to escape predators. The clapper rail is one of six rail species found in North Carolina. The others include the sora, Virginia, king, black and yellow rail. Even with this variety of rail species, the clapper rail is likely only to be confused with the king rail, a slightly larger bird that prefers freshwater marshes. The clapper rail is listed as a game bird and can be hunted in North Carolina.

Description

The clapper rail is one of the largest rail species, 13 to 16 inches in length. They can be distinguished by their chicken-like appearance, long unwebbed toes, long decurved bill and frequent upturned tail with white under tail covert feathers. Clapper rails are olive-brown or gray-brown, with vertical gray-white barred flanks and buff or rust-colored breasts. The subspecies found along the Atlantic Coast generally has a paler appearance than other populations. Males are slightly larger than females but similar in coloration. Juveniles are generally more uniformly colored than adults. Clapper rails produce an astounding variety of calls, the most notable being kek-kek-kek or chock-chock-chock. Regardless of the interpretation, the primary call is loud and clattering in a series of 20 to 25 notes, lowering in pitch and increasing in tempo. Females have been heard to give a “purr” call.

History and Status

Clapper rails were once abundant; however, egg collecting and market hunting in the 1800s and early 1900s reduced rail populations significantly. There are accounts of more than 120 eggs being collected in a day by a single person. Now, thanks to modern game laws, eggs cannot be collected and light hunting pressure appears to have no permanent effect on rail populations. Instead, population size is most affected on a year-to-year basis by the flooding of nests from high tides in spring. The long-term population trend of the bird will be most severely affected by water pollution and the destruction of coastal marsh habitat. Due to the rail’s secretive nature, the difficulty of working in marsh environments, and a lack of funding for rail research, basic information regarding life history and yearly population status is still somewhat limited.

Habitat and Habits

Clapper rails are found almost exclusively in coastal saltwater marshes. Observing clapper rails can be difficult because the birds prefer to run through thick marsh grass rather than fly. When they do take to the air, clapper rails are considered weak flyers and generally settle down shortly after taking flight. The nesting season occurs from April to June. Nests, built mostly by males, are clumps of vegetation and are often found where ditches or creeks cause the occurrence of tall and short grasses. Common nesting materials are rushes, sedges and cordgrass. Generally, nine to 12 eggs are laid. Some rails may produce second clutches. Incubation averages 20 days, and it’s probably performed by both sexes. The young are semi-precocial and are able to feed independently shortly after leaving the nest. Young rails are able to fly in nine to 10 weeks. Clapper rails prefer more of an animal-based diet than other rail species.

People Interactions

Though their chattering call is often heard, rails are not often seen except by avid bird-watchers or hunters. Best viewing opportunities occur at dawn and dusk as the birds leave the thick marsh grass and feed on open mud flats. Rail season opens in early September but hunting pressure and harvest is minimal. Human-related activities that have the most negative impact on rail populations are development and pollution of coastal marsh habitats. Clapper rail populations can best be protected by preserving these key areas.

NCWRC Interaction

Although definitive population data for clapper rails is limited, populations along the east coast appear stable. However, development of coastal habitats and resulting pollution presents the greatest long-term threat facing this secretive species. The key to the long-term conservation of clapper rails (and other rail species) is protection of coastal marsh habitat through the strong support of effective wetland protection laws. Currently, researchers are testing the ability to monitor rail populations with call-back surveys. The survey involves playing a pre-recorded call of a particular rail species and then listening for “call-backs.” The survey has promise to determine presence/absence of the species and long-term population trends.

References:

Bent, Arthur C. Life Histories of North American Marsh Birds (Dover Pub., Inc., 1963)

Farrand, J. The Audubon Society Master Guide to Birding—I. Loons to Sandpipers (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1983)

Johnsgard, P. A. North American Game Birds of Upland and Shoreline (Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1975)

Ripley, Dillon. Rails of the World (David Godine, 1977)

Tacha. T.C. and C.E. Braun. Migratory Shore and Upland Game Bird Management in North America (International Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, 1994).

Credits:

Photos by Maslowski Photography and Larry Hitchens Photography. Illustrations by J.T. Newman.

Produced 2011 by the Division of Conservation Education; Cay Cross–Editor.

1 January 2011 | Fuller, Joe