Slave Clandestine Economy

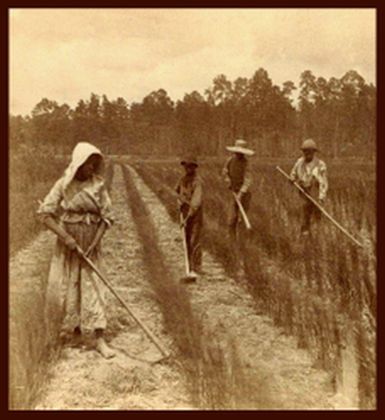

Slave clandestine economy refers to a variety of private agricultural and business endeavors undertaken by some North Carolina enslaved people. In 1771 a Scottish visitor to North Carolina was somewhat surprised to find that the daily routine of people enslaved on plantations included time for them to work "in their own private fields, consisting of 5 or 6 acres of ground, allowed them by their enslaver, for planting rice, corn, potatoes, tobacco, &c." The visitor was describing the task system of labor of enslaved people that endured from long before the American Revolution until the Civil War, for enslavers often permitted their bondsmen and women time to cultivate their own garden plots. The system benefited both enslavers, who used it as an incentive, and enslaved people, who could supplement their meager diets with vegetables and fruits. It also led to participation by the people in the enslaved population in secret economic activities such as bartering crops for whiskey or wine, unloading their surplus to other Black people who acted as factors, and selling cash crops to local merchants.

Slave clandestine economy refers to a variety of private agricultural and business endeavors undertaken by some North Carolina enslaved people. In 1771 a Scottish visitor to North Carolina was somewhat surprised to find that the daily routine of people enslaved on plantations included time for them to work "in their own private fields, consisting of 5 or 6 acres of ground, allowed them by their enslaver, for planting rice, corn, potatoes, tobacco, &c." The visitor was describing the task system of labor of enslaved people that endured from long before the American Revolution until the Civil War, for enslavers often permitted their bondsmen and women time to cultivate their own garden plots. The system benefited both enslavers, who used it as an incentive, and enslaved people, who could supplement their meager diets with vegetables and fruits. It also led to participation by the people in the enslaved population in secret economic activities such as bartering crops for whiskey or wine, unloading their surplus to other Black people who acted as factors, and selling cash crops to local merchants.

That these practices flourished in the early national period was demonstrated on three occasions between 1779 and 1788, when state legislators rewrote a law of 1742 prohibiting enslaved people from "dealing and Trafficking." It was their intention to prevent people in enslavement from buying, selling, trading, bartering, or borrowing "any Commodities whatsoever." Judging by later petitions to the General Assembly from concerned citizens and subsequent laws, "dealing and Trafficking" by enslaved people were not curtailed; indeed, as time went on they seem to have increased.

Although many enslaved people probably had access to a garden plot and traded or bartered at one time or another, sometimes even with their enslaver's permission, a small number of them participated in the more sophisticated aspects of the clandestine economy. Unlike its neighbors to the north, North Carolina did not develop iron and coal industries that could employ significant numbers of people who were enslaved, although it did participate fully in hiring of enslaved people. Hired Black enslaved people sometimes received limited extra compensation for their work beyond the contract payment to the enslaver; at other times they actually worked for wages. Commenting on the effect of paying wages to enslaved people, famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted wrote that "negroes in the swamp [making shingles] were more sprightly and straightforward in their manner and conversation than any field hand plantation negroes that I saw." From the owners there were no complaints of "'rascality' or laziness." Working for wages permitted people who were enslaved to purchase various commodities and even to own property.

Wages also made it possible for a few ambitious enslaved people to move into a "gray area" between slavery and freedom, either by hiring themselves out or accumulating enough money to gain some independence. The Society of Friends (Quakers) and other antislavery groups helped to perpetuate these practices by purchasing enslaved people and allowing them "virtual freedom." Those who opposed them often petitioned the General Assembly for new laws to stop the uncontrolled movement of people in enslavement, or they filed suit against a particular African American; however, such charges were difficult to prove, and judges sometimes sided with Black people who had acquired a "reputation for freedom." Self-hired and virtually free, they often were among the most skilled and talented Black residents and engaged in a variety economic activities, including trade with plantation enslaved people. They worked as carpenters, coopers, cabinetmakers, masons, fishermen, market women, and even contractors.

In 1802 white mechanics in New Hanover County asked the North Carolina legislature to prohibit enslaved people from working as free mechanics and undertaking contracts "on their own account, at sometimes less than one half the rate that a regular bred white mechanic could afford to do it." According to their petition, enslaved people occasionally hired gangs of 8 to 12 other bondsmen and bondswomen who worked entirely "for their own benefit." Half a century later, quasi-free enslaved people contractors in the county still conducted a brisk construction business.

Such activities, of course, were unusual, as most people in enslavement labored for their enslavers in the tobacco, rice, or cotton fields. Although the extent of the clandestine slave economy has not been thoroughly studied, there is little doubt that a significant number of enslaved people in North Carolina participated in various business undertakings that were neither condoned by their enslavers nor permitted under the law.

Reference:

John Hope Franklin, "Slaves Virtually Free in AnteBellum North Carolina," Journal of Negro History 28 (July 1943).

Image Credit:

"Georgia rice field workers." Original image available from DocSouth, UNC (https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/coffin/menu.html). Available from http://www.learnnc.org/lp/media/uploads/2009/05/rice_field_slaves.jpg (accessed May 4, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Schweninger, Loren