Janet Schaw traveled from her homeland of Scotland to the West Indies and then North Carolina in 1774. She documented the journey in her diary, which was later published as Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776. During her time in North Carolina she visited her brother Robert Schaw at his plantation along the Cape Fear River, Schawfield, as well as other plantations. Her journals provide insight into the Loyalist perspective in the months before the Revolutionary War as well as commentary on the agricultural practices in place at the time. Below is a transcription of her journal from her visit to Schawfield.

Nothing can be finer than the banks of this river; a thousand beauties both of the flowery and sylvan tribe hang over it and are reflected from it with additional lustre. But they spend their beauties on the desert air, and the pines that wave behind the shore with a solemn gravity seem to lament that they too exist to no purpose, tho' capable of being rendered both useful and agreeable. For those noble trees that might adorn the palaces of kings are left to the stroke of the thunder, or to the annihilating hand of time, and against whom the hard Sentence (tho' innocent of the crime) may be pronounced, why cumber ye the ground? As that is all that can be said of them in their present state that they cover many hundred, nay thousand acres of the finest ground in the universe, and give shelter to every hurtful and obnoxious animal, tho' their site is a most convenient situation both for trading towns and plantations. This north west branch is said to be navigable for Ships of 400 tons burthen for above two hundred miles up, and the banks so constituted by nature that they seem formed for harbours, and what adds in a most particular manner to this convenience is, that quite across from one branch to the other, and indeed thro' the whole country are innumerable creeks that communicate with the main branches of the river and every tide receive a sufficient depth of water for boats of the largest size and even for small Vessels, so that every thing is water-borne at a small charge and with great safety and ease.

But these uncommon advantages are almost entirely neglected. In the course of sixteen miles which is the distance between these places and the town, there is but one plantation, and the condition it is in shows, if not the poverty, at least the indolence of its owner. My brother indeed is in some degree an exception to this reflection. Indolent he is not; his industry is visible in every thing round him, yet he also is culpable in adhering to the prejudices of this part of the world, and in using only the American methods of cultivating his plantation. Had he followed the style of an East Lothian farmer, with the same attention and care, it would now have been an Estate worth double what it is. Yet he has done more in the time he has had it than any of his Neighbours, and even in their slow way, his industry has brought it to a wonderful length. He left Britain while he was a boy, and was many years in trade before he turned planter, and had lost the remembrance of what he had indeed little opportunity of studying, I mean farming. His brother easily convinced him of the superiority of our manner of carrying on our agriculture, but Mrs. Schaw was shocked at the mention of our manuring the ground, and declared she never would eat corn that grew thro' dirt. Indeed she is so rooted an American, that she detests every thing that is European, yet she is a most excellent wife and a fond mother. Her dairy and her garden show her industry, tho' even there she is an American. However he has no cause to complain. Her person is agreeable, and if she would pay it a little more attention, it would be lovely. She is connected with the best people in the country, and, I hope, will have interest enough to prevent her husband being ruined for not joining in a cause he so much disapproves.

I have just mentioned a garden, and will tell you, that this at Schawfield is the only thing deserving the name I have seen in this country, and laid out with some taste. I could not help smiling however at the appearance of a soil, that seemed to me no better than dead sand, proposed for a garden. But a few weeks have convinced me that I judged very falsely, for the quickness of the vegetation is absolutely astonishing. Nature to whose care every thing is left does a vast deal; but I remember to have read, tho' I forget where, that Adam when he was turned out of paradise was allowed to carry seeds with him of those fruits he had been suffered to eat of when there, but found on trial that the curse had extended even to them; for they were harsh and very unpalatable, far different from what he had eat there in his happy state. Our poor father, who from his infancy [alternative reading, from his first creation] had been used to live well, like those of his descendents, was the more sensible of the change, and he wept bitterly before his beneficent Creator, who once more had pity on him, and the compassionate Angel again descended to give him comfort and relief. "Adam," began the heavenly messenger, "the sentence is passed, it is irrevocable; the ground has been cursed for your sake, and thorns and briers it must bring forth, and you must eat your bread with the sweat of your brow, yet the curse does not extend to your labours, and it yet depends on your own choice to live in plenty or in penury. Patience and industry will get the better of every difficulty, and the ground will bear thistles only while your indolence permits it. The fruits also will be harsh while you allow them to remain in a state of uncultivated nature; because man is allowed no enjoyment without labour; and the hand of industry improves even the choicest gifts of heaven." Adam bowed in grateful acknowledgment, and his heavenly instructor led him forth to the field, and soon taught him that God had given him power over the inanimate as well as the animate part of the creation, and that not only every beast and every bird was under his command, but that he had power over the whole vegetable world; and he soon proved that the hand of industry could make the rose bloom, where nature had only planted the thistle, and saw the fig-tree blossom, where lately the wild bramble was all its boast. He taught him that not only the harsh sourness of the crab was corrected, but the taste and flavour of the peach improven; by the art of ingrafting and budding the pear became more luscious, and even the nectarine juice was poor and insipid without this assistance. Adam had no prejudices to combat, he gave the credit due to his heavenly instructor, and soon saw a new Eden flourish in the desert from his labours, and eat fruit little inferior to those he had left, rendered indeed even superior to his taste by being the reward of his honest Industry.

As I cannot produce my Authority, perhaps you may suspect I have none, but that it was coined for the present purpose, should you think so, I cannot help it, but should Gabriel himself assure the folks here that industry would render every thing better, they would as little believe him, as they would your humble servant. Truly the only parable they mind is that of the lily of the Valley, which they imitate as it toils not, neither does it spin, but whether their glory exceeds that of Solomon is another question, but certain it is they take things as they come without troubling themselves with improvements. I have as yet tasted none of their fruits, but am told that notwithstanding the vast advantages of climate, they are not equal in flavour to those at home in our gardens,--on walls which indeed they have no occasion for. Wherever you see the peach trees, you find hard by a group of plumbs so fit for stocks, that nature seems to have set them there on purpose. But her hints and the advice of those who know the advantages of it are equally unregarded. There are also many things that are fit for hedges, which would be a vast advantage, but these straggle wild thro' the field or woods, while every inclosure is made of a set of logs laid zagly close over each other.

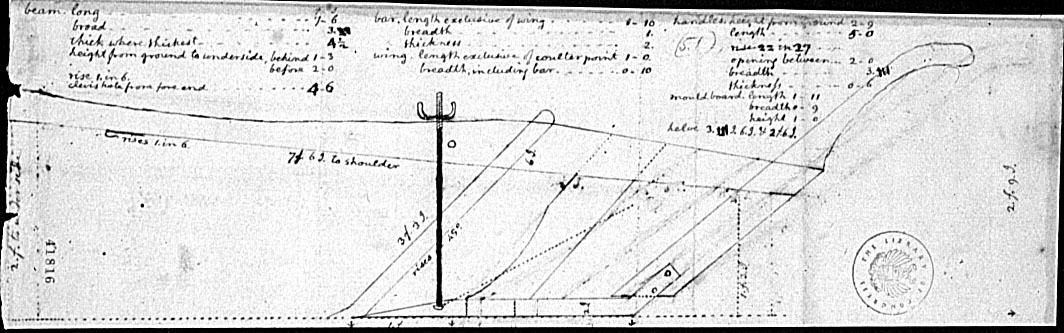

On our arrival here the stalks of last year's crop still remained on the ground. At this I was greatly surprised, as the season was now so far advanced, I expected to have found the fields completely ploughed at least, if not sown and harrowed; but how much was my amazement increased to find that every instrument of husbandry was unknown here; not only all the various ploughs, but all the machinery used with such success at home, and that the only instrument used is a hoe, with which they at once till and plant the corn. To accomplish this a number of Negroes follow each other's tail the day long, and have a task assigned them, and it will take twenty at least to do as much work as two horses with a man and a boy would perform. Here the wheel-plough would answer finely, as the ground is quite flat, the soil light and not a stone to be met with in a thousand acres. A drill too might easily be constructed for sowing the seed, and a light harrow would close it in with surprising expedition. It is easy to observe however from whence this ridiculous method of theirs took its first necessary rise. When the new Settlers were obliged to sow corn for their immediate maintenance, before they were able to root out the trees, it is plain no other instrument but the hoe could be used amongst the roots of the trees, where it was to be planted, and they were obliged to do it all by hand labour. But thro' this indolence some of them have their plantations still pretty much incumbered in that way, yet to do justice to the better sort, that is not generally the case. Tho' it is all one as to the manner of dressing their fields, the same absurd method continuing every where. If horses were hard to come at or unfit for labour, that might be some excuse, but far is it otherwise. They have them in plenty, and strong animals they are and fit for the hardest labour.

Primary Source Cited:

Schaw, Janet. Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press. Published electronically by Documenting the American South. University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/schaw/menu.html