By Megan Morrow, SLNC Government and Heritage Library, July 2023

ca. 1738 - June 25, 1792

The person known as Thomas Peters (Potters, Petters) was born around the year 1738 and likely in present-day Nigeria. Thomas Peters was given his name by a captain on a slave ship. His original name and the members of his family are unknown. Peters was born into a wealthy Nigerian family. They were members, and potentially nobility, of the Egba branch of the Yoruba tribe. French enslavers brought Peters to French Louisiana from present-day Nigeria on the slave ship Henri Quatre. He was sold to a French planter and tried three times to escape while in Louisiana. He was caught each time, and his enslaver branded and flogged him as punishment. Around 1760, a Scotsman named William Campbell in Wilmington, North Carolina bought Peters. Peters became a millwright in Wilmington. Millwrights were mechanics who worked on heavy machinery. While there, he also met his wife, Sally. Together they had a daughter, Clairy, born in 1771, and a son, John, born in 1781.

The British monarchy issued many Acts in the 1760s, including the Stamp Act. Many colonists hated the Acts and wanted independence from Britain. By April 1775, calls for independence had developed into war. The American Revolution placed Patriots against Loyalists. Patriots wanted independence. Loyalists wanted to remain with Britain. Wilmington was a large city at this time and many people there had conflicting ideas of loyalty during the Revolution. Both sides wanted people to fight for their cause and offered rewards for doing so. In November 1775, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation. It offered freedom to any enslaved person or indentured servant that was “able and willing to bear arms” in support of Britain.

On February 9, 1776, the British sloop Cruizer moved up the Cape Fear River to bomb Wilmington. The city was evacuated. More British ships arrived from Boston under the command of Sir Henry Clinton. The British ships attacked the city, and riverside homes and plantations. The destruction allowed many enslaved people to escape freely. Peters’s enslaver fled, and he was no longer technically enslaved. It was here that Peters, his wife, and daughter allied with the British. They wanted to take their freedom back. In 1776, a captain under Clinton named George Martin grouped the freed people from the Cape Fear area into a military company. It was known as the Black Pioneers. They helped maintain supplies and create defenses for the British. They served in the war until the surrender of Yorktown, Virginia. Thomas Peters was sworn into the Black Pioneers on November 14, 1776, at New York. He swore the following oath of loyalty:

“I Thomas Peters do swear that I enter freely and voluntarily into His Majesty’s Service and I do enlist myself without the least compulsion or persuasion into the Negro Company commanded by Captain Martin and I will cheerfully obey all such directions as I may receive from my said captain…so help me God.”

Martin served as captain of the Black Pioneers. The unit had a sum of about seventy men. There were three Black sergeants and at least one Black corporal in the Black Pioneers unit. Peters and Murphy Steele were two of the sergeants. The Black Pioneers received the same pay as other provincial soldiers. Peters was paid one shilling a day for being a sergeant. During his time in the Black Pioneers, Peters was twice injured by the Patriots.

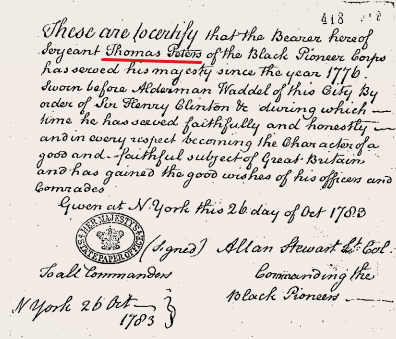

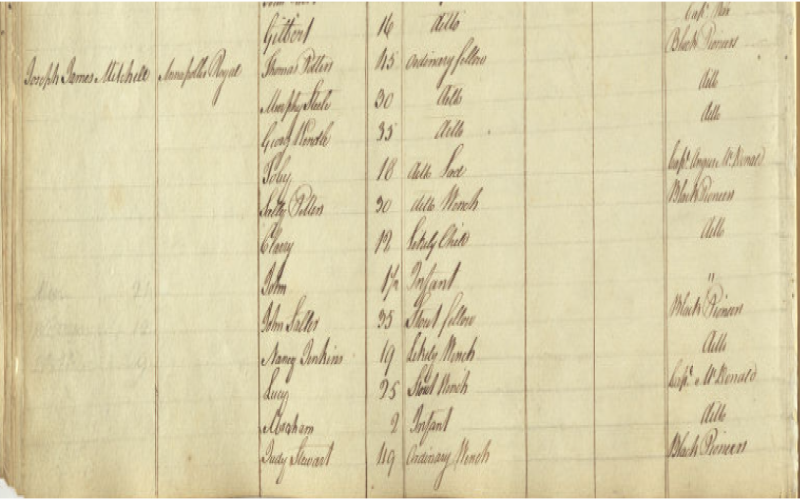

The British began evacuating the United States after their defeat in the war. About 3,000 Black Loyalists and others left New York City for British Canada. Peters’ evacuation was part of a group of 67 Black Pioneers, servants, and manual laborers for the King’s army. It consisted of 21 men, 28 women and 18 children. Peters, along with Sally, Clairy, and John, traveled to Nova Scotia in November 1783. They sailed on a ship called Joseph under captain James Mitchell. Peters carried with him a passport “to all commanders.” It attested to his faithful and honest service to the British Army. Strong winds blew the Joseph off course. This forced the ship and its passengers to dock in Bermuda for the winter. The Joseph and its passengers did not reach Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia until May 25, 1784.

The British government promised food, land, tools, and free travel to Loyalists evacuated from New York when they arrived in Nova Scotia. The aid promised would decrease each year, with the first year’s installment being a year’s supply of food for free. The aid was designed to help the Loyalists until they were able to settle in Nova Scotia, grow crops, and build their own supply of meat. The first year of food was delayed. When it finally arrived, they received only enough food to last 80 days. This barely lasted through the end of the summer. It was not enough for Nova Scotia's harsh winter. Conditions were harder still for the Black Loyalists. Officials placed them into racially segregated villages. They had poor land where little would grow. White Nova Scotians were also very prejudiced against Black Nova Scotians. They sometimes destroyed their homes and farms, or even re-enslaved free Black Nova Scotians. Black Nova Scotians often worked hard jobs for low wages.

Thomas Peters and Murphy Steele both settled in a suburb of Annapolis Royal called Digby. They became leaders of the community. White and Black Nova Scotians competed for land in Digby. Peters and Steele also petitioned Governor John Parr. They wanted better land than what was offered in the racially segregated villages. Parr ignored their petitions. Racial tension in Nova Scotia became worse. Peters went to New Brunswick and even asked their governor, Guy Carleton, for their own land:

“That your Petitioner and Numbers of other Blacks are unprovided with Lands, he humbly implores in the name of the whole that something May be done for them as he and many others are suffering. Their present Situation is Such that they are incapable of paying the poor tax.”

Peters also worked in St. John, New Brunswick for about six years as a millwright. Conditions were very harsh and many Black Canadians struggled. The British government was not fulfilling its promises of a better life for those who assisted the King during the Revolution.

Many years of failed petitions and requests from Black Canadians demanded action. About 200 Black families across Canada asked Peters to carry their pleas to London. Peters left Halifax to petition the British government in London in the summer of 1790. When he arrived there, a series of debates over the Transatlantic slave trade were taking place. The United Kingdom did not abolish the slave trade until 1807. However, the debates helped the position of Black Loyalists like Peters. A bill to establish the Sierra Leone Company was passed in 1791. The company would manage a new colony in West Africa. It would serve Black Loyalists of the American Revolution. Peters helped negotiate the terms of the Company’s involvement in the colony. He negotiated in London for about a year before returning to Nova Scotia. Peters met and worked with many powerful abolitionists in Britain, like Granville Sharp and John Clarkson. Peters returned to Halifax from London in fall 1791.

White Nova Scotians did not like the idea of creating a free state in West Africa for Black Loyalists in Canada. If the Black laborers left Nova Scotia, white Nova Scotians would have to do the hard jobs themselves. Black Nova Scotians supported the idea, as it promised freedom. Peters and John Clarkson, now in Nova Scotia, gathered support for the colony through church sermons and petitions. By the end of 1791, about 1200 Black Canadians agreed to return to West Africa with the Sierra Leone Company. On January 15, 1792, roughly 1200 Black Canadians left Halifax for West Africa. The journey was hard, and about 70 people died during the trip. Fifteen ships transporting Black Loyalists and company administrators arrived by March 9, 1792. They docked on the coast of modern-day Sierra Leone.

The crews began building housing using materials from their ships. Peters reported the successful landing to the British government:

“We…desire to return our Sincere Thanks to your Lordship, and to our greatest Sovereign, for the Faviours [sic] we have received in our removal from Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone.

We are intirely Satisified, with the place and the climate…The treatment we received on our passage was very good; but our Provisions was ordinary; we was allowed Salt Fish four Days in a week and one half was Spoilt, the Turnips also no use to us, for the great part of them was Spoilt…”

The message Peters sent also showed that the colony was struggling with supplies. Problems started to arise again for the colonists and they looked to Peters for help. Peters and Clarkson also debated over who should lead the colony. This threatened the new state. Clarkson feared that too many people supported Peters.

The Black Loyalists that came to Freetown were very upset about the problems they were encountering. They had been promised new land and civil rights in the new colony, and neither had happened. Clarkson feared Peters was causing trouble by making too many promises. Around the same time, Peters was accused by a jury of theft when trying to collect a debt, and was found guilty. The court sentence was likely politically motivated. Arguments over the colony continued. Soon Peters became sick, with Clarkson’s records noting that he “appears far from well” on June 16, 1792. By June 23, Peters was too sick to leave his home, and Peters died a few days later, at 54 years old, on June 25, 1792.

Peters helped create a modern nation in Sierra Leone, even though the colony struggled during his lifetime. His final resting place is in Freetown, Sierra Leone. A statue of Thomas Peters is located at St. George’s Cathedral in Freetown.

Glossary:

- Enslaver: Someone that takes or keeps a person in slavery

- Patriot: Supporters of independence during the American Revolution

- Loyalist: Supporters of the British monarchy in the colonies during the American Revolution

- Nova Scotia, New Brunswick: Territories of East Canada

- Sierra Leone Company: British company responsible for creating a free state in West Africa for Black people.

- Abolitionist: Someone that wanted to abolish slavery

Guided Reading Questions

- In what North Carolina city did Thomas Peters escape slavery?

- True or False: Black Nova Scotians were treated poorly after the Revolution.

- What was the purpose of the Sierra Leone Company?

References:

Brooks, George E. “The Providence African Society’s Sierra Leone Emigration Scheme, 1794-1795: Prologue to the African Colonization Movement.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 7, no. 2 (1974): 183–202. https://doi.org/10.2307/217128.

Crow, Jeffrey J. The Black Experience in Revolutionary North Carolina. Raleigh: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History. 1977.

Gilbert, Alan. Black Patriots and Loyalists : Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2012.

Hodges, Graham Russell Gao and Alan Edward Brown, eds. The Book of Negroes : African Americans in Exile After the American Revolution. New York: Fordham University Press, 2021.

Kup, A. P. “John Clarkson and the Sierra Leone Company.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (1972): 203–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/217514.

Lee, Enoch Lawrence. The Lower Cape Fear in Colonial Days. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 1965.

MacKinnon, Neil. This Unfriendly Soil : The Loyalist Experience in Nova Scotia 1783-1791. Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986.

Moss, Bobby Gilmer and Michael C. Scoggins. African American Loyalists in the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution. Blacksburg, South Carolina: Scotia-Hibernia Press, 2005.

Nash, Gary B. "Thomas Peters: Millwright and Deliverer." In Struggle and Survival in Colonial America, edited by David G. Sweet, Gary B. Nash, 72-73. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, Berkeley, 1981. https://revolution.h-net.msu.edu/essays/nash.html.

Philips, Caryl and Simon Schama. Rough Crossings. London: Oberon Books. 2017.

Wilson, Ellen Gibson. The Loyal Blacks. New York: Capricorn Books. 1976.