Legal Challenges to Imprisonment of Japanese American Citizens

Detaining American citizens in prison camps aroused constitutional and legal challenges from would-be prisoners. Approximately 70,000 of the prisoners were American citizens, thus imprisoning them violated established constitutional and legal protections including the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments as these people had committed no crimes. During the period of internment, there were four legal challenges that made their way to the Supreme Court, seeking to preserve the rights of Japanese American people that were held captive by the U.S. government.

Hirabayashi v. United States, 1943

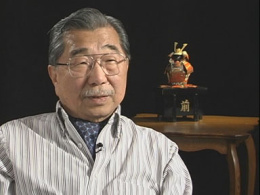

The first Supreme Court case involving imprisoned Japanese American citizens was the case of Gordon Hirabayashi. Hirabayashi, an American-born citizen of Japanese descent, was a pacifist who disapproved of the war and opposed the imprisonment of Japanese American people. To demonstrate his opposition to imprisonment based solely on ethnic identity, Hirabayashi refused to comply with the curfew set by the War Department that required all people of Japanese ancestry to be within the confines of their homes from 8 pm to 6 am daily. When the removal orders were announced, Hirabayashi turned himself in to the Seattle FBI, citing that he would not comply with the removal orders as they violated the Constitution. He hoped to create a test case that would establish the forced movement and imprisonment of Japanese and Japanese American people as unconstitutional. Hirabayashi was arrested, then charged with two crimes: refusal to comply with the curfew imposed on people of Japanese Ancestry and refusal to comply with the “military zone” boundaries established by the War Department. Hirabayashi was found guilty of both charges, and was sentenced to 60 days in prison. Hirabayashi negotiated with the court to receive a sentence on a road camp so that his prison sentence could be served outdoors, and the request was granted, with his sentence lengthened to 90 days. After receiving the 90 day sentence, Hirabayashi’s lawyers appealed and the case made its way to the United States Supreme Court. Although he was tried on two crimes, the court only heard his case concerning the curfew. The charges were upheld by the Supreme Court in Hirabayashi v. United States, thus legal precedent was set that people of particular ancestry could be subjected to different regulations in times of war due solely to their racial or ethnic identity.

When it came time to serve his sentence, Hirabayashi experienced further challenges.There was no transportation in place to transfer Hirabayashi to his assigned road camp, even though this sentence was assigned to him by a judge. Thus, Hirabayshi had to convince legal officials to allow him to hitchhike from Washington to Arizona to serve his sentence, where he again had to convince officials that he was there to serve a sentence as they were unable to locate the appropriate records. During his prison sentence, Hirabayashi also experienced the same problems other Japanese American people faced concerning the loyalty questionnaire and draft orders. Hirabayshi refused to comply with both the questionnaire and draft orders, and legally represented himself when charged with refusing to comply with the orders. He received a one year sentence for his refusal to complete the questionnaire and enroll in the draft. In 1987, Hirabayashi v. United States was reopened on the basis of government misconduct, such as hiding or destroying evidence pertinent to the trial of Hirabayashi. The court ruled in favor of Hirabayashi in 1987.

Yasui v. United States, 1943

The case of Yasui v. United States was heard and decided by the United States Supreme Court concurrently with Hirabayashi v United States. Minoru Yasui, an American-born Portland attorney who had worked for the Japanese consulate in the United States, decided to challenge the constitutionality of the curfew. On March 28, 1942, Yasui broke the 8 p.m. curfew and presented himself at the police station at 11:00 pm in an effort to test the curfew’s constitutionality. The District Court ruled that the curfew could not be applied to citizens of the United States because marshal law had not been issued, but Yasui had given up his citizenship when he worked with the Japanese consulate from 1940-1941, a position from which he resigned on December 8, 1941, the day after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. When Yasui’s case made it to the Supreme Court, the court ruled that Yasui had not given up his United States citizenship, but that the lower court had ruled incorrectly that citizens were not subject to the curfew. The Supreme Court again supported the constitutionality of the curfew applying only to people of Japanese descent in Yasui v. United States, and returned the case to the lower court for sentencing.Yasui was sent to the Minidoke prison camp in Idaho.

Korematsu v. United States, 1944

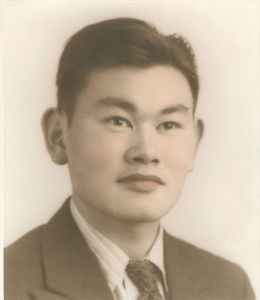

Korematsu v. United States (1944) was another defeat for Japanese American legal and citizenship rights. Fred Korematsu, a California-born child of Japanese immigrants, lived within one of the military zones outlined by the War Department that excluded Japanese Americans. Prior to internment, Korematsu had actively worked to support a pro-U.S. stance in the war effort; he attempted to enlist in the military as early as 1940 but was rejected, and was repeatedly fired from positions that benefitted the war effort – such as shipbuilding – due to his Japanese nationality. When General Dewitt ordered curfews and confined zones for Japanese American people in March 1942, Korematsu underwent plastic surgery to appear more European or white, so that he would not be suspected of breaking the curfew or violating the military exclusion zone. In early May 1942, when Dewitt announced all Japanese American people must report for relocation and imprisonment, Korematsu’s family left Military Area No. 1 to report. But Korematsu stayed behind. He was arrested for not complying with the relocation policy. Korematsu’s arrest and charges were upheld by the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States, 1944. Associate Justice Hugo Black’s delivery underscored that the court’s opinion maintained that military necessity took precedence over civil rights: "Korematsu was not excluded from the military area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire," and "because they decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast temporarily."

In 1983, the case was reopened with evidence of government misconduct, which influenced the ruling given in the 1944 decision. The government had knowingly destroyed or hidden evidence which stated that Japanese civilians were of no threat to military operations. Korematsu’s name was cleared on November 10, 1983 by the federal district court in San Francisco, California, despite the Supreme Court ruling remaining in effect.

Ex Parte Endo, 1944

Japanese American imprisonment was finally ended by the Supreme Court in 1944 with their Ex Parte Endo (1944) decision. Mitsuye Endo was the daughter of Japanese immigrants and a prisoner of the Tule Lake, California facility. Before imprisonment, she worked in a clerical position (office support, such as answering phones and filing papers) with the state Department of Employment in California. A series of legal actions by the state of California fired their Japanese American employees, Endo included. The Japanese American Citizens League focused on Endo’s case because it represented significant issues that imprisonment ignored. Endo was a Christian, had worked for the government, spoke only English, had never even visited Japan, making her imprisonment wholly unjustifiable to supporters of Japanese American Imprisonment. This legal challenge escalated to the Supreme Court, where in the 1944 Ex Parte Endo decision the Supreme Court ordered the conditional release of all wartime prisoners of Japanese descent. The Ex Parte Endo decision found that a proven, “loyal” American citizen could not be held prisoner. With the decision, Endo was permitted to leave the Topaz, Utah facility where she had been held.

The conditional release granted within Ex Parte Endo required a successful completion of the questions in the Loyalty Questionnaire administered in 1943. The Loyalty Questionnaire was a test given only to Japanese American prisoners that affirmed their willingness to support the United States and serve the armed forces. However, the nature of the questionnaire was problematic, as only Japanese American people had to pass it, and some of the questions within it were intentionally confusing and oddly worded to disadvantage those to whom it was given. Particularly, the hypothetical and all-or-none nature of Question 27 asking “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” and Question 28 asking “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?” worried and confused prisoners who were given it. They were worried what implications were given if answering “Yes” and/or “No” to either question. Renouncing the emperor and Japan removed the opportunity for imprisoned Japanese American people to be able to return to Japan after the war. The issue of swearing loyalty to the United States and forsaking Japan often divided families (especially those with Nisei parents/grandparents who were ineligible for citizenship) and led to some Issei Japanese American people renouncing their citizenship in order to be able to return to Japan after the war to support their families. Those that answered “No” for each question were nicknamed “No-nos” and were usually relocated to the Tule Lake high security detention facility for those that “failed” the Loyalty Questionnaire.