Industrialization needed five things -- capital, labor, raw materials, markets, and transportation -- and in the 1870s, North Carolina had all of them. This article explains the process of industrialization in North Carolina, with maps of factory and railroad growth.

In 1860, North Carolina was an agricultural state, with only scattered industry and a handful of towns with a population of more than 1,000. By 1900, hundreds of factories -- most of them tobacco and textile mills -- were transforming the Piedmont.

How and why did industry grow in North Carolina after the Civil War? Industrialization needed five things -- capital, labor, raw materials, markets, and transportation -- and in the 1870s, North Carolina had all of them.

Capital

Capital -- money -- was the first thing needed to establish a factory. North Carolinians had lost a great deal of money and property in the Civil War, but there was still money to be invested. Some prewar mills survived and grew, and their owners invested the profits in new factories. Planters could no longer invest their money into enslaving others as laborers, and agriculture was becoming less profitable. After the war, planters and farmers with money to invest increasingly put that money into industrial development. Many industrialists started quite small, with only a little savings and borrowed money, and built their businesses slowly. Merchants, meanwhile, increasingly sold goods to farmers and industrial workers that people had once made at home, and they, too, could invest their profits in new factories.

Labor

Who worked in North Carolina's factories? North Carolina, like other southern states, had a tremendous supply of cheap labor. Recently-emancipated Black people and their free-born children were often eager to escape the plantation for new opportunities in cities, even if they earned less than their white counterparts and were often given only menial jobs -- sweeping up, for example, instead of operating complex machinery. And North Carolina had always had a large share of landless white laborers who found they preferred working in a factory to sharecropping.

As families moved to new mill villages, women and children, too, took jobs in factories. Children were especially likely to work in textile mills, where they could easily learn to tend machines.

Raw materials

North Carolina's main industries turned the state's agricultural products into finished goods. Today, a factory may buy its raw materials from anywhere in the world, but North Carolina's nineteenth century industries stayed a little closer to home. By the early twentieth century, the state's economy was dominated by three industries. You can think of them as the three T's: tobacco, textiles, and timber (or furniture).

Tobacco

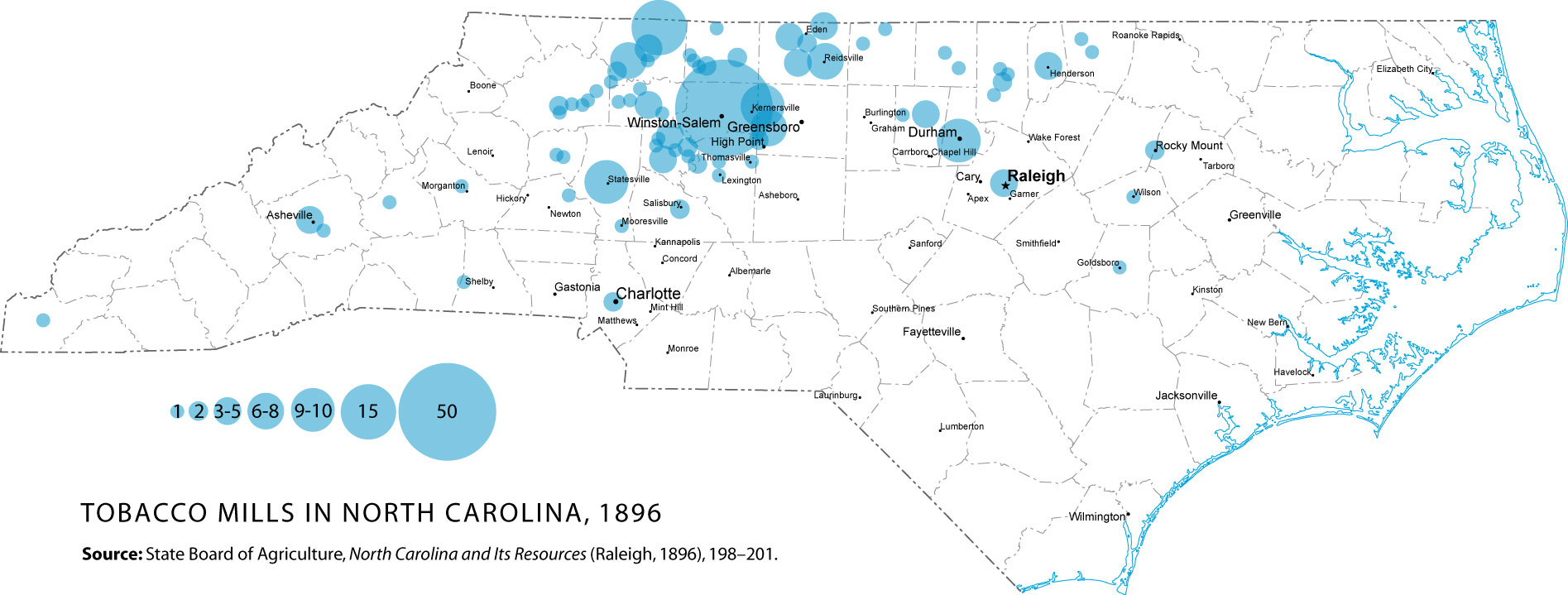

Tobacco mills turned raw tobacco grown on North Carolina farms into cigars, chewing tobacco, and cigarettes that were sold nationwide. By 1896, the state Board of Agriculture reported 242 tobacco mills in North Carolina. Among them were the Duke operations in Durham and those of R. J. Reynolds in Winston-Salem.

Textiles

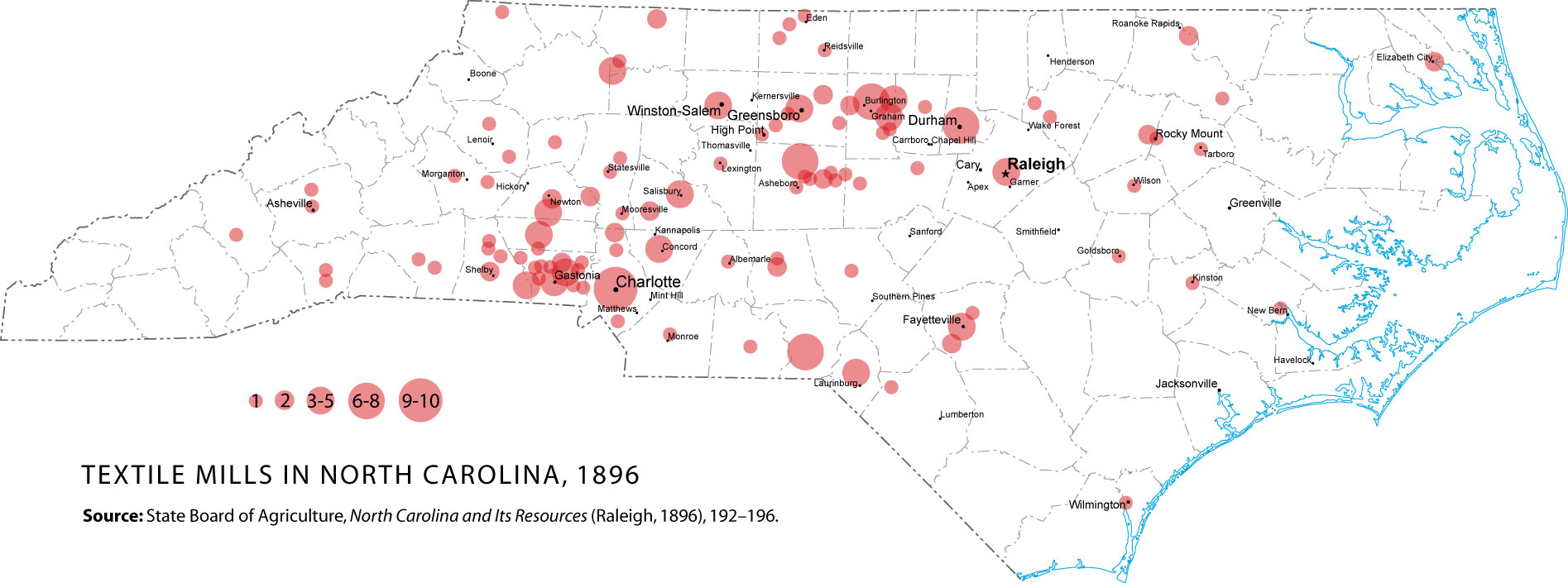

Textile mills turned raw cotton and, to a lesser extent, wool into clothing that was also sold to consumers nationwide. Before the war, the South had shipped its cotton to the North and to Europe; now, North Carolina's textile mills processed the state's staple crop, and North Carolinians kept the profits. The Cone Mills in Greensboro and Hanes Mills in Winston-Salem are two names you may know, but by 1896 there were 182 cotton mills in North Carolina, as well as 10 woolen mills.

Furniture (timber)

North Carolina had not only an extensive pine forest, but great hardwood forests as well. As with cotton and tobacco, the state had long sent its timber to the North for processing. But in the 1880s, Earnest Ansel Snow began buying lumber from those forests, building furniture in a factory in High Point, and selling it to consumers across the country. Soon, High Point factories were building furniture for the Sears Roebuck mail-order catalog. By 1900, the area around High Point had become the furniture capital of the United States.

Pine and spruce forests, meanwhile, were being cut down for paper. So much timber was harvested, in fact, that in 1898 George Washington Vanderbilt would open the Biltmore Forest School to find ways to preserve North Carolina's mountain forests.

Markets

Where did all these factory-made goods go? Many went to consumers in northern (and, increasingly, southern) cities -- middle-class and working-class people who no longer made their own clothing and other household goods, and who had extra income to spend on store-bought goods. Department stores and discount "five and dime" stores sprang up during this time, to serve the new urban markets. By the 1890s, farm families, too, could buy factory-made goods, through new mail-order catalogs. And although tobacco had always been widely used, now it became highly fashionable, thanks in part to cigarettes and new forms of advertising. By 1900, Americans spent more on tobacco than they did on clothes!

Transportation

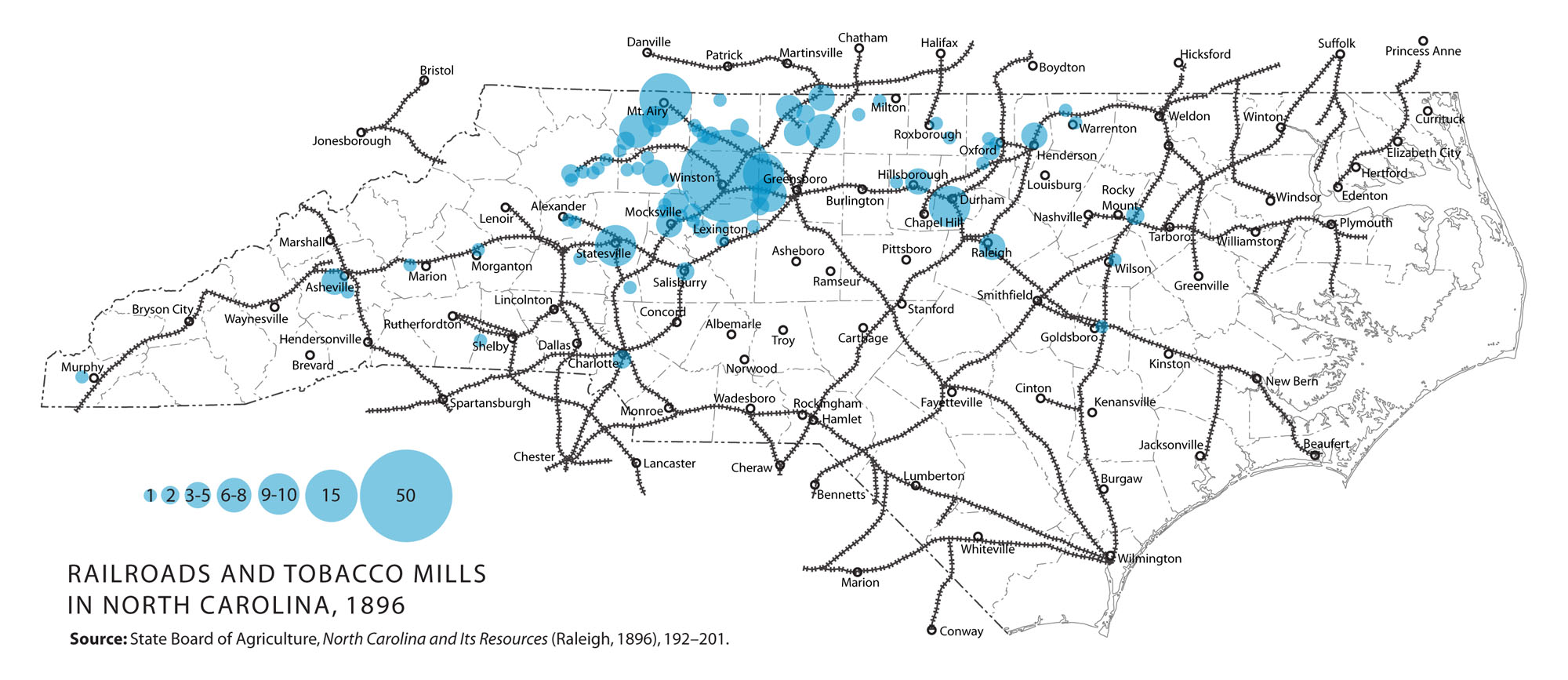

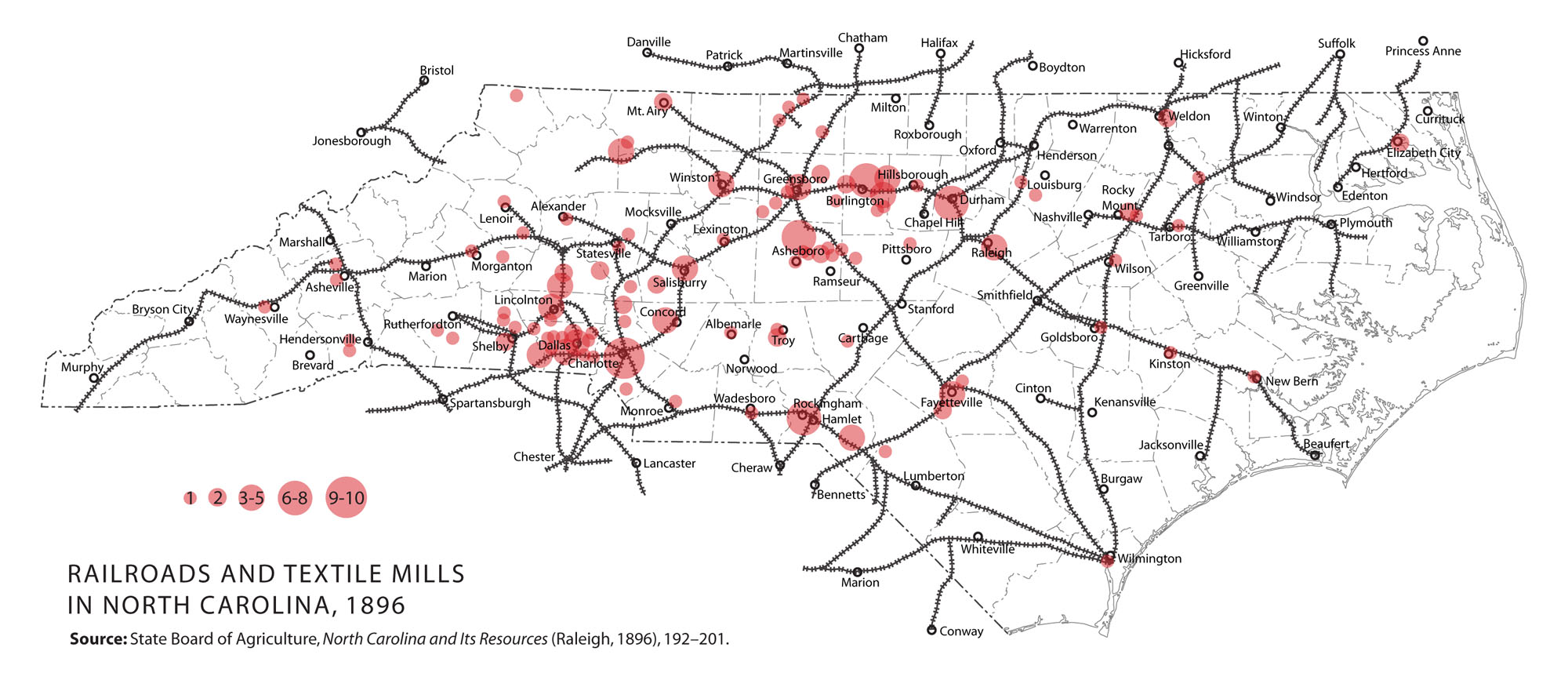

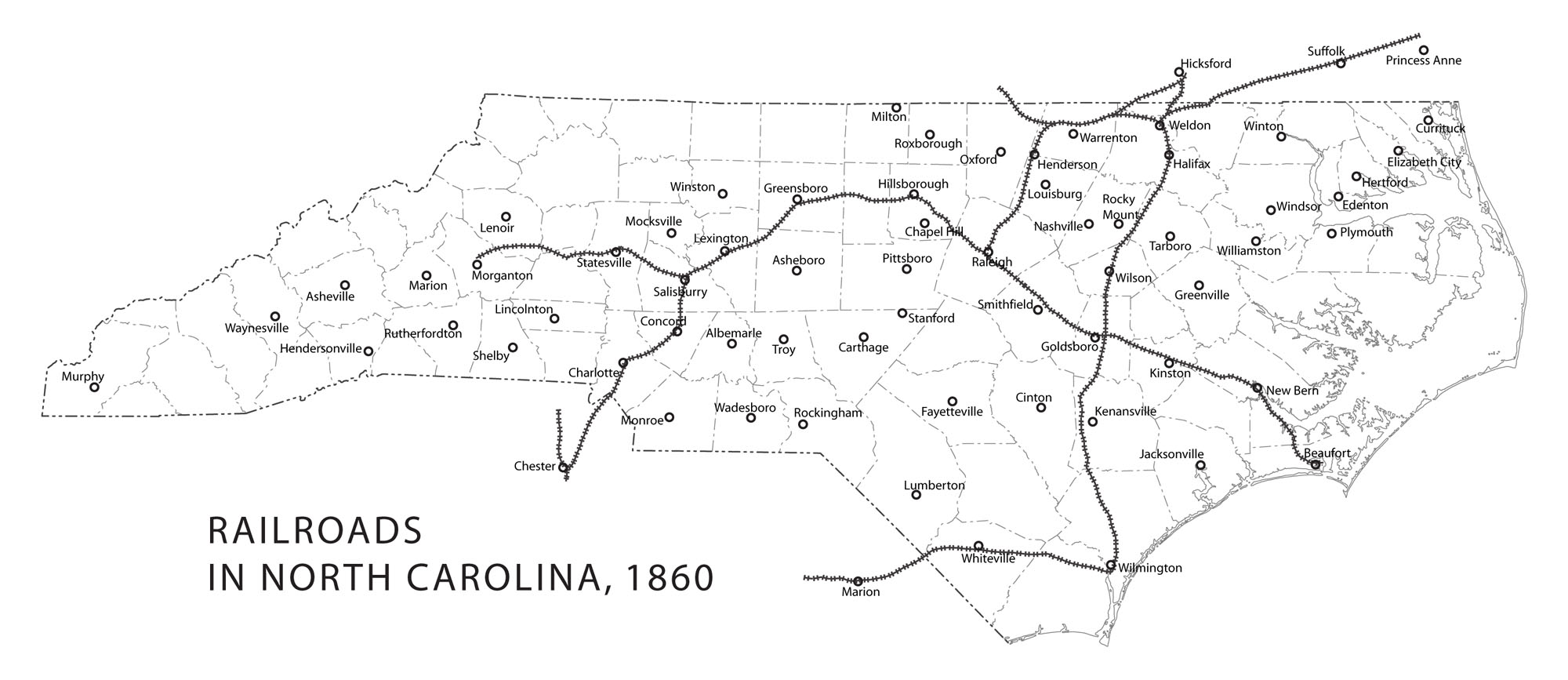

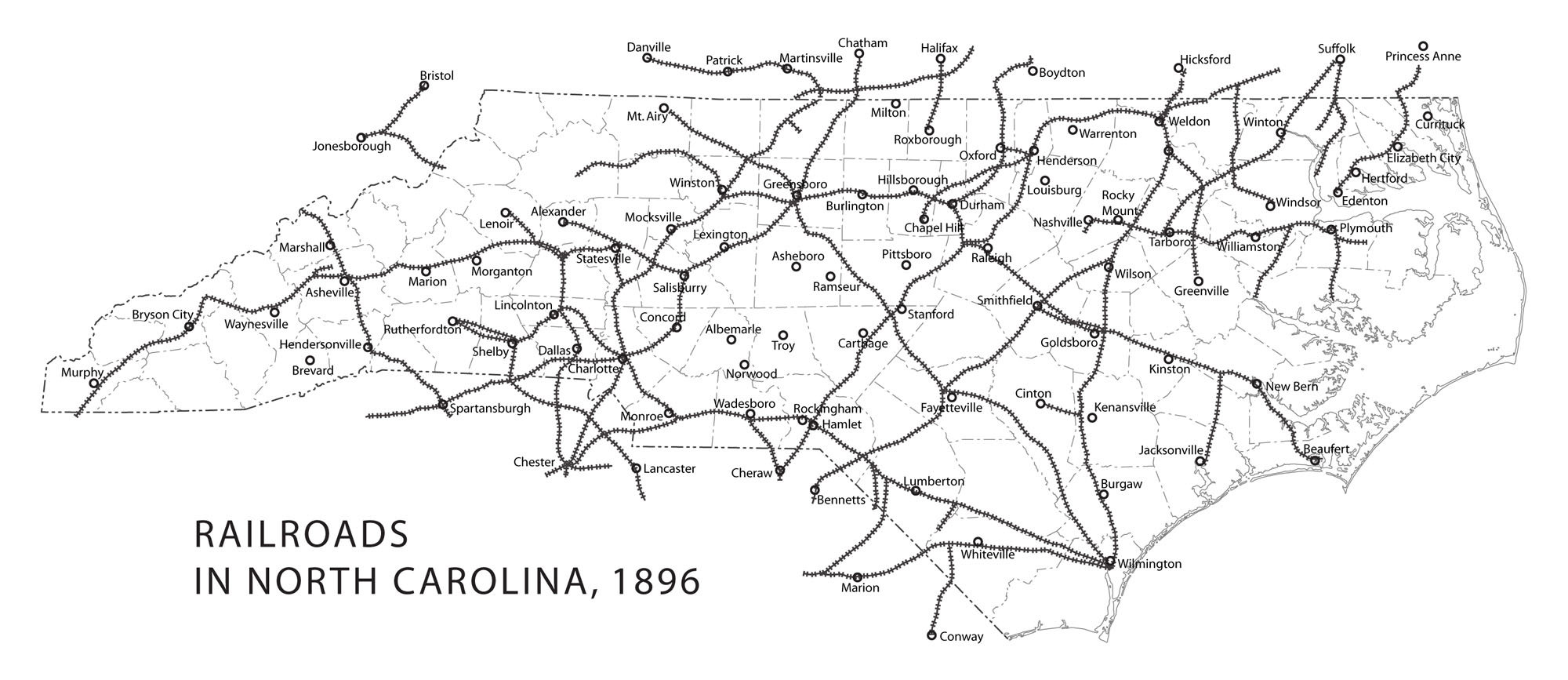

Factories needed good transportation to get raw materials and to send finished goods to markets elsewhere in the country. After the Civil War, North Carolina's railroads grew rapidly, spurred at first by Republican policies during Reconstruction. By the end of the century, the state was criscrossed by railroads.

Railroads in North Carolina, 1860 (top) and 1896.

Just how important were railroads to the growth of industry? See what the maps of textile and tobacco mills look like if we add railroads:

Investors built factories with easy railroad access. And when several factories existed in one place, that town grew, and if it wasn't already served by a railroad, it soon would be.