Slavery

See also: Ad Valorem Taxation of Enslaved people; Colonization Societies; Manumission Societies; Slave Clandestine Economy; Slave Codes; Slave Names; Slave Narratives; Slave Patrols; Slave Rebellions; State v. John Mann; State v. Negro Will; Underground Railroad.

Slavery was an important part of the history of the state of North Carolina. Most enslaved people that were brought to the Carolina colony in the late 1600s by their enslavers were from Guinea (West Africa). Direct importation of enslaved people was not as extensive as in other southern colonies, but was still a large part of the eastern North Carolina's early economy. With the increased demand for cash crops in European markets and the subsequent need for fertile land, the British Lords Proprietors in 1663 offered additional acreage for every enslaved person brought into Carolina during the first five years of white colonization. The labor-intensive cash crops of tobacco, rice, and indigo made the use of enslaved labor a "necessary" solution to the inadequate labor supply in the early eighteenth century. Most of this need was met through the natural increase (enslaved families raising enslaved children) of populations of enslaved people, which outpaced direct imports by 1720. After the Carolinas officially split in 1729, North Carolina had 6,000 enslaved people within its borders. Comparatively, South Carolina had about 32,000.

Slavery was an important part of the history of the state of North Carolina. Most enslaved people that were brought to the Carolina colony in the late 1600s by their enslavers were from Guinea (West Africa). Direct importation of enslaved people was not as extensive as in other southern colonies, but was still a large part of the eastern North Carolina's early economy. With the increased demand for cash crops in European markets and the subsequent need for fertile land, the British Lords Proprietors in 1663 offered additional acreage for every enslaved person brought into Carolina during the first five years of white colonization. The labor-intensive cash crops of tobacco, rice, and indigo made the use of enslaved labor a "necessary" solution to the inadequate labor supply in the early eighteenth century. Most of this need was met through the natural increase (enslaved families raising enslaved children) of populations of enslaved people, which outpaced direct imports by 1720. After the Carolinas officially split in 1729, North Carolina had 6,000 enslaved people within its borders. Comparatively, South Carolina had about 32,000.

Geographic barriers made slave trading difficult in North Carolina but they did not totally prevent it. The port at Wilmington was used extensively in the trans-Atlantic slave trade to the Lower Cape Fear region. However, the barrier islands along the northern coast did not permit access to the natural harbors from the Atlantic Ocean, making the direct importation of enslaved people into the northern part of the Carolina colony virtually impossible. Many enslavers in North Carolina purchased enslaved people via overland routes from South Carolina, Georgia, and the Chesapeake region.

Geographic barriers made slave trading difficult in North Carolina but they did not totally prevent it. The port at Wilmington was used extensively in the trans-Atlantic slave trade to the Lower Cape Fear region. However, the barrier islands along the northern coast did not permit access to the natural harbors from the Atlantic Ocean, making the direct importation of enslaved people into the northern part of the Carolina colony virtually impossible. Many enslavers in North Carolina purchased enslaved people via overland routes from South Carolina, Georgia, and the Chesapeake region.

Agricultural patterns determined the distribution of enslaved people in North Carolina. The Lower Cape Fear was colonized in the 1720s by South Carolina planters who used the labor of enslaved people to produce rice and naval stores. Enslavement was also prevalent along a tier of counties bordering Virginia that concentrated on the cultivation of tobacco. By 1860, 19 counties in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont had populations with Black people as the majority, and 12 of these 19 counties produced at least 1,000 400-pound bales of cotton. Commercial crops depended heavily on the labor of enslaved people. Even in the North Carolina Mountains, where it was impossible to grow staple crops, enslaved people engaged in a variety of economic activities, including manufacturing, mining, construction, and livestock management.

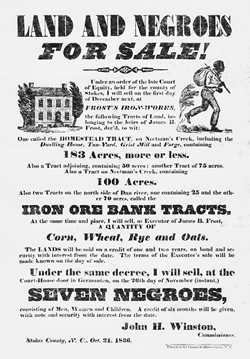

At the time of the French and Indian War (1754-63), an enslaved person cost approximately £60 to £80. During the 1780s the price escalated to as much as £180. An enslaved African person in Charles Towne (Charleston, S.C.), bound for North Carolina, brought $300 in 1804. By 1840, an enslaved person considered "a prime field hand" cost about $800. Twenty years later enslaved people considered field hands sold for $1,500 to $1,700, enslaved women $1,300 to $1,500, and enslaved artisans as much as $2,000.

As the American Revolution produced a temporary lull in the slave trade, the natural population increase of enslaved people led to southern states selling enslaved people at a profit. North Carolina attempted to reduce importation of enslaved people as early as August 1774, when the Provincial Congress meeting in New Bern resolved "that we will not import any slave or slaves, or purchase any slave or slaves, imported or brought into this Province by others, from any part of the world, after the first day of November next." This prohibition of the slave trade is repeated several times in North Carolina records.

By the end of the Revolutionary War, the nation sought to regain economic stability by reopening the African and West Indian slave trade, especially in the Carolinas and Georgia. This action met with increased resistance in the Upper South states of the Chesapeake area and in North Carolina, partly because it would cut into profits of interregional trade and partly because of the mainly imagined fear that slave rebellions would spread from the West Indies.

In 1786, North Carolina again banned importation of enslaved people; it increased the prohibitive duty on imported enslaved people, which was later repealed in 1790. Prohibitive laws became more specific in 1794, barring the importation not only of enslaved people but also of indentured servants by "land or water routes." One year later, legislators passed the "Act against West Indian Slaves," which expressly prevented the importation of enslaved people by individuals emigrating from the West Indies. White enslavers in North Carolina made up 31 percent of the population in 1790 and 27.7 percent in 1860. 2 percent of these enslaved more than 50 people, and only 3 percent attained the rank of planter (enslaving 20 or more people). In 1860, the vast majority of enslavers (70.8 percent) enslaved about 10 people.

In 1800 and 1807 Congress barred U.S. citizens  from exporting enslaved people, and as of January 1, 1808 it prohibited any engagement in the international slave trade. What to do with "confiscated slaves" was left up to individual states. In 1816 North Carolina and several other states passed the Act to Dispose of Illegally Imported Slaves, opting to sell all enslaved people who had been imported after 1808 with the proceeds benefiting the state treasury.

from exporting enslaved people, and as of January 1, 1808 it prohibited any engagement in the international slave trade. What to do with "confiscated slaves" was left up to individual states. In 1816 North Carolina and several other states passed the Act to Dispose of Illegally Imported Slaves, opting to sell all enslaved people who had been imported after 1808 with the proceeds benefiting the state treasury.

Although federal and state laws banned the importation of enslaved people nationwide, these same laws kept the prices high for enslaved people in the Lower South. The "need" for enslaved labor in the Cotton Belt, the natural population increase of enslaved people , and the stagnant economy of the Upper South in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries all bolstered the interregional slave trade. Between 1810 and 1820, 137,000 enslaved people were sent from the Chesapeake states and North Carolina to Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The sluggish economy of the 1820s-30s led to the sale of thousands more enslaved people from North Carolina to the Cotton Belt.

By any measure, most enslaved people were ill-fed, ill-housed, and ill-clothed. In the 1780s, Johann David Schoepf, a traveler observed: "The keep of a negro here does not come to a great figure, since the daily ration is but a quart of maize, and rarely a little meat or salted fish." Schoepf also reported that each year an enslaved man received "a suit of coarse woolen cloth, two rough shirts, and a pair of shoes." Conditions had scarcely improved during the antebellum period. Enslaved people supplemented their owner-supplied diet of cornmeal and fat pork by hunting, fishing, and raising vegetable gardens. Dark, smoky, and crowded, cabins for enslaved people were insubstantial structures with dirt floors, unglazed windows, and wattle-and-daub chimneys.

Despite their abhorrent conditions, enslaved people tried to preserve families and develop cultural defenses against white oppression and enslavement. Conversion to Christianity before the Revolution came slowly; enslaved people continued to worship African spirits and to practice African rituals such as the "ring shout." A nineteenth-century observer, who witnessed a Jonkonnu celebration at Somerset Place plantation in Washington County, compared the celebration to a Muslim festival that he had attended in Egypt. Nevertheless, by the nineteenth century Christianity was the religion of many enslaved people. Baptists and Methodists proved especially effective in converting enslaved people, who then adapted Christian practices and teachings to their own purposes. Black people founded separate churches in Fayetteville, Wilmington, New Bern, and Edenton. Some enslaved people conducted prayer meetings in secret. One formerly enslaved person recalled a practice that probably derived from West African ceremonies: "We turned down pots on the inside of the house at the door to keep master and missus from hearing the singing and praying."

In the eighteenth century, enslaved people continued to use an extensive pool of culturally-significant African names for their children, but by the nineteenth century their naming patterns showed strong family ties. Enslaved people were named for fathers, grandfathers, aunts, and uncles. African crafts, medicine, conjury, dance, music, song, and folklore endured. Such cultural persistence allowed enslaved people to construct their own value system, which their enslavers never could entirely suppress.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, North Carolina's more than 360,000 newly emancipated Black Americans continued these traditions in various forms. In the immediate aftermath of war, African Americans sought precisely those rights and freedoms that had been denied them while enslaved: normalization of marriage, equal political and civil rights, education, and the right to own property. With freedom came new opportunities but also numerous new hardships, rooted in white people's deep and brutal acrimony toward Black people's social, economic, and political pursuits.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: Voices from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/VoicesTransAtlanticSlaveTrade.pdf

Grade 8: United States Constitution of 1787 & Slavery. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://database.civics.unc.edu/files/2012/05/USConstitutionandSlavery1.pdf

References:

Jeffrey J. Crow, Paul D. Escott, and Flora J. Hatley, A History of African Americans in North Carolina (2002).

John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss Jr., From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans (6th ed., 1988).

Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 (1976).

Everett Jenkins Jr., Pan-African Chronology: A Comprehensive Reference to the Black Quest for Freedom in Africa, the Americas, Europe, and Asia, 1400-1865 (1953).

Marvin L. Michael Kay and Lorin Lee Cary, Slavery in North Carolina, 1748-1775 (1995).

Michael Tadman, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (1989).

Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870 (1997).

Additional Resources:

Fountain, Daniel L. “A Broader Footprint: Slavery and Slaveholding Households in Antebellum Piedmont North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 91, no. 4 (2014): 407–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44113225.

Smith, John David. “‘I Was Raised Poor and Hard as Any Slave’: African American Slavery in Piedmont North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2013): 1–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523655.

Image Credit:

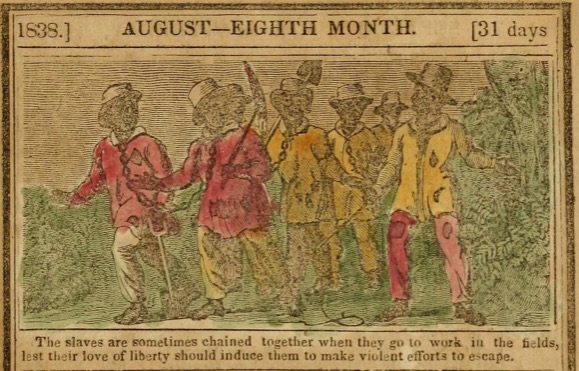

llustration of slaves in chains. From Southern, N., American Antislavery Almanac (August 1838). Boston: Isaac Knapp, Publisher. https://archive.org/details/americanantislav1838chil/page/20/mode/2up

llustration of slaves under the overseer's whip. From Southern, N., American Antislavery Almanac (August 1838). Boston: Isaac Knapp, Publisher. https://archive.org/details/americanantislav1838chil/page/20/mode/2up

1 January 2006 | Crow, Jeffrey J.; Dees-Killette, Amelia; Huff, Diane